ENERGY GIVES RUSSIA

Of all the lessons one might draw from Russia's bullying of Ukraine, this may be the most coldblooded of all: If you want to behave badly, it helps to have a lot of oil and gas. Much will be forgiven, or at least ignored.

European nations, international energy companies and China are all, in their own ways, driving home the point. The Europeans are afraid of pushing economic sanctions against Moscow too far lest they be cut off from the Russian natural gas that provides a significant share of their energy.

The international energy companies are busy reassuring the Russians that they will keep working to help develop Russian energy supplies, the Ukraine crisis notwithstanding.

And the Chinese—well, they may be on the verge of completing a deal that has been under negotiation for 10 years to begin buying a lot of Russian natural gas. Russian officials said last week that they expect the negotiations to be completed before Russian President Vladimir Putin visits China in May.

For Mr. Putin, a China deal would amount to a multibillion-dollar strategic security blanket. If European nations to Russia's west don't want to buy his gas because of his annexation of Crimea and intimidation of Ukraine, never mind. He soon will have a large market for his gas to the east as an alternate.

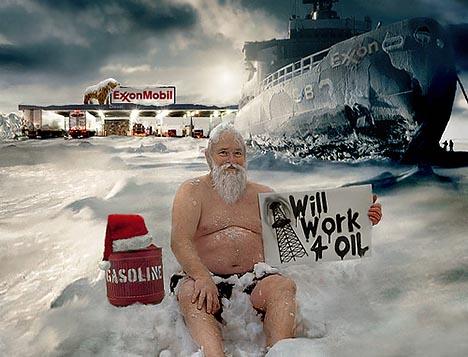

At the outset of the Ukraine crisis, it seemed possible that its impact on Russia's energy-based economy might be different. Sen. John McCain said, only half jokingly, that Russia is a "gas station masquerading as a country," and therefore should be uniquely vulnerable to sanctions because its economy sits on such a narrow and precarious base.

The masquerade, though, may turn out to be a pretty good one. It's true that Russia badly needs the revenue from energy sales—and modest sanctions appear to have prompted some outflow of capital from Russia—but Moscow's customers appear to feel equally vulnerable. In an interview with the Washington Post's Lally Weymouth a few days ago, Poland's foreign minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, said that "today's strategic commodity in Europe is gas, and we take about 30% of our gas from Russia, as does Europe. But we overpay because Russia has managed to create monopolistic arrangements."

Mr. Sikorski and his Polish colleagues are more hard-nosed than most about the Russians. He says Russia needs Polish money more than Poland needs Russian natural gas, and he called for an energy union in Europe to create some more security.

But he also said in the interview that economic ties are "why we are reluctant to impose sanctions on Russia. We would rather Russia stop doing what is giving rise to the need for sanctions."

Meanwhile, international oil companies show little sign of reconsidering their energy arrangements with Russia. In recent days, executives of Royal Dutch Shell, BP and Statoil all have indicated they are pushing ahead with—and in some cases expanding—projects they have launched to develop Russian oil and gas.

Bob Dudley, BP's chief executive, said that Western sanctions would have no impact on his company's business and that his firm remains "rock solid with its investment in Russia." BP has a 19.75% stake in the state-controlled Rosneft oil company.

Meanwhile, China's leaders undoubtedly are torn between conflicting impulses over Russia's behavior in Ukraine. On one hand, China, fearful of ferment among ethnic groups on various points along its country's borders, long has been a stickler for respecting territorial integrity and internationally recognized borders. The idea of giving indigenous groups within a sovereign state the right to cite cultural or ethnic factors as a rationale for breaking away—the justification Russia used to seize Crimea—can't be a pleasing precedent for Chinese leaders.

On the other hand, if Russia has a new incentive to diversify its energy customer base away from its traditional European clients, the energy-hungry Chinese seem happy to oblige. So it was telling that Russian media last week quoted a deputy prime minister, Arkady Dvorkovich, as saying the decadelong effort to negotiate a deal to ship Russian gas to China is near completion. On top of that, he said, the two countries also are interested in more Russian oil exports to China as well as energy projects in Crimea—the very piece of Ukraine that Russia has essentially swallowed.

What lessons might there be for the U.S. in all of this?

In the short run, the developments illustrate why it will be tough to persuade allies to increase sanctions on Russia.

In the long run, perhaps the situation can create new motivation for the U.S. to achieve real energy independence, plus the ability to go further and help allies ease their own dependence on both Middle Eastern oil and Russian natural gas.

wsj.com