DON'T KNOW TO DO

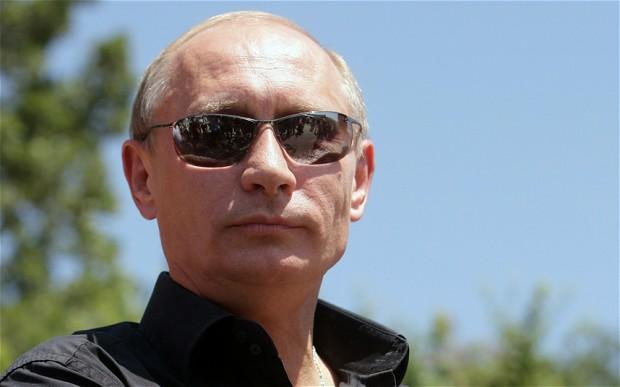

When you do not know what to do, you do what you know. The other day I heard an astute observer of Vladimir Putin's Kremlin attach this aphorism to Moscow's hostility towards the west. Confronted with the unknown, the Russian president has taken refuge in the familiar.

The thought of Nato marking retreat from Afghanistan by picking a fight with Moscow is beyond risible. The strategic challenges for Russia lie elsewhere: economic stagnation, crumbling physical and social infrastructure, demographic decline and separatist insurgents. If he is looking for threats without, Mr Putin would do better to turn east.

Russia's oil and gas revenues are fighting a losing battle against industrial decay, social deprivation and capital flight. Mr Putin's brutal victory in the second Chechen war did not bring peace to the north Caucasus: the Kremlin is fighting a guerrilla war in Dagestan and rising Islamist extremism elsewhere.

Just as Mr Putin does not have a plan for the Caucasus, he does not know how to deal with a fast-growing and energy-hungry China as it rubs up against depopulation in petrocarbon-rich Siberia. He can pretend the two nations represent a rival power bloc to the west; and he can sell gas to Beijing at knockdown prices. Missing is a strategy to reverse Russian decline in its emptying east.

The one thing Mr Putin does know, as my Russian acquaintance reminded me, is how to treat the west as an existential threat. Seared by the chaos of the 1990s, he probably does harbour some real grievances. For an alumnus of the KGB, though, blaming Russia's troubles on the US and Nato is always the default option. The record has worn thin in the playing: Washington broke its promises not to extend Nato's reach into the former Soviet space; the International Monetary Fund wrecked the Russian economy.

Russia's annexation of Crimea and its foray into eastern Ukraine were opportunistic responses to the collapse of always vain hopes for a Eurasian Union to compete with the EU. Beyond destabilising the Kiev government, Moscow does not have a road map. The bills for Crimea are already arriving in Moscow and, as the Kremlin has discovered, its Russian-speaking proxies in eastern Ukraine sometimes have minds of their own. Mr Putin has stirred the embers of nationalism. His personal ratings have soared. Only for now.

Europe, in its own way, has also been trying to keep hold of the familiar. The continent's leaders saw the collapse of the Soviet Union as a chance to extend their postmodern political model to the Urals and beyond. The new Russia, they assumed, would want to integrate with the west. Mr Putin has decided otherwise, but his neighbours are reluctant to admit as much. For all the rhetoric about the threat to the post-1945 order posed by the invasion of Crimea, they still want to see him as they imagined he would become.

These leaders have forgotten how to be tough, losing sight of the distinction between resolve and provocation. Mr Putin wants to relive the cold war; Europeans have overlooked one of its most important lessons. The purpose of standing tough against the Soviet Union was not to start a fight, but prevent one.

This summer's elections to the European Parliament measured rising popular anger with high unemployment, austerity and globalisation. It seems obvious enough that EU governments have only a few years to come up with an answer to the continent's ills. The acute crisis in the eurozone has passed, but its future rests on it becoming at once economically coherent and politically sustainable. France has to be persuaded to modernise its economy. Beyond the euro, Britain has to be rescued from its isolationist delusions.

You would not have divined such an agenda in the response to the elections of the political elites. They want the Europe they know, so they have spent the weeks since polling day locked in negotiations about the share-out of the EU's top jobs. Arguing about who leads the European Commission or who takes the chair at summits is a lot easier than confronting the realities of a different world. The elites assumed that the new order would be multilateral as well as multipolar. China, India, Brazil and the rest have taken a different view. Never mind, they can always argue about whether this or that job should be filled by a Christian Democrat or a Socialist, a man or a woman.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Barack Obama has been having a rather different wrestling match with history. The president first won office with a pledge to withdraw from Iraq. Now US troops are back. His predecessor had been defined by the attempt to extend US power. Mr Obama has focused on the limits. Much of what he says about a changed US role sounds intelligent enough. But over-analysis begets paralysis. The history lesson from the 1920s is that an isolationist America can be every bit as destabilising as an overmighty one.

If there is a thread through some of this, it is a failure of imagination: in Russia and Europe, an attempt to cling on to old certainties; in the US, a reluctance to sketch out a global role that sits between hegemony and complete withdrawal. Unwilling to confront the world as it is becoming, these leaders are hanging on to what they know.

Visiting London last month, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang reprised the familiar dictum that those who fail to learn the lessons of history are destined to repeat it. There is something in this. One of the lessons, though, is that you sometimes have to let go of the past.

ft.com