U.S. SHALE OVER

BLOOMBERG - For years, Opec ignored the rise of the US shale industry and came to regret its mistake. Now, the group is making another bold gamble on America's oil revolution: that its golden age is over.

When the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries meets this week, ministers will discuss whether to extend their current output target, rather than reduce it, according to people familiar with the internal debate.

The reason?

They believe relentless US oil production growth will slow rapidly next year.

Opec isn't alone. Across the industry, oil traders and executives believe US production will grow less in 2020 than this year, and at a significantly slower rate than in 2018. On paper, the cartel has the oil market under control.

Brent crude has been trading around $60 a barrel for most of 2019, about 14% higher than at the start of the year but well below the peak of $75.60 a barrel set in late April.

But Opec and its allies should be wary of discounting competition from US shale and other non-Opec suppliers.

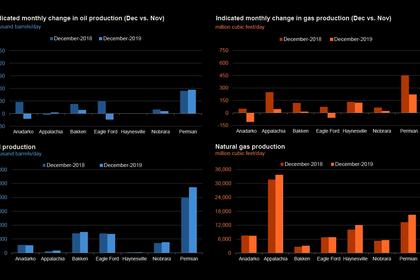

Total US oil production reached an all-time high of almost 17.5mn barrels a day in September, up 1.3mn barrels a day from a year earlier. That expansion is likely to continue at least into the beginning of 2020 before slowing down.

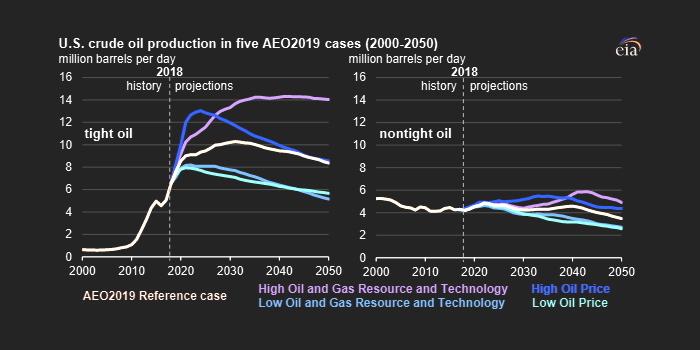

Slower growth doesn't mean no growth, however. While the independent companies which drove America's shale expansion are struggling, and have announced big spending cuts, Big Oil is now playing a much bigger role in key basins such as the Permian. Companies with deeper pockets, such as Exxon Mobil Corp and Royal Dutch Shell Plc are likely to continue spending, increasing production in Texas, New Mexico and elsewhere.

Vitol Group, the world's largest independent oil trader, expects US production to increase by 700,000 barrels a day from December 2019 to December 2020, compared to growth of 1.1mn barrels a day from the end of 2018 to the end of 2019.

Perhaps the biggest problem for Opec isn't American shale but rising output elsewhere. Brazilian and Norwegian production is increasing, and will advance further in 2020. After several years of low prices, engineers have made many projects cheaper, and the results are clear.

Norway's Johan Sverdrup oil field, the biggest development in decades in the North Sea, started up earlier this year, months ahead of schedule and several billion dollars under its original budget. And Guyana, a tiny country bordering Venezuela in Latin America, is about to pump oil for the first time.

"For Opec, it remains a difficult first half of 2020," Russell Hardy, Vitol's chief executive officer, said in an interview. "US production is growing strongly this quarter and in the first half of next year we'll add non-Opec production from Norway, Brazil and Guyana."

The group knows well that it's taking a gamble. The group's own estimates show that if it continues pumping as much as it has done over the last couple of months – roughly 29.9mn barrels a day – it would supply about 200,000 barrels more crude daily than the market needs on average next year. The oversupply would be concentrated in the first half, when Opec estimates it needs to pump just 29mn barrels a day to prevent oil stocks building up.

Iraq said on Sunday that Opec and its allies would consider deeper production cuts, though the comments come after the coalition has widely signalled reluctance to take such action.

Other Opec officials, speaking privately, believe the world's supply and demand balance could be tighter than many expect - a big change from the past three years. They see non-Opec output growth falling short of forecasts while global demand increases could be higher than expected.

"The market's fear of a global recession has receded," said Vitol's Hardy. "There are problems here and there, but in general the music hasn't stopped and demand didn't follow the 2008 model" when it slumped amid the financial crisis.

And the crude market is, right now, relatively tight, giving Opec some solace that it would be able to weather the first few months of 2020 when it will loosen up a bit. The tightness is particularly acute for the kind of oil that most Middle East nations pump: lower quality so-called heavy-sour oil.

The fact is that the oil market isn't just crude: other petroleum liquids, such as so-called condensate and natural gas liquids – which are by-products of oil and gas drilling – are abundant. Condensate and NGLs are processed into refineries, and often blended with fuels such as gasoline and also used to produce petrochemical industry feedstock naphtha.

"The crude oil balance for next year shows a tight market," said Amrita Sen, chief oil analyst at London-based consultant Energy Aspects Ltd. "But when you add other liquids, like condensates, then the balance is looser."

-----

Earlier: