SOUTH AFRICA'S OIL & GAS RULES

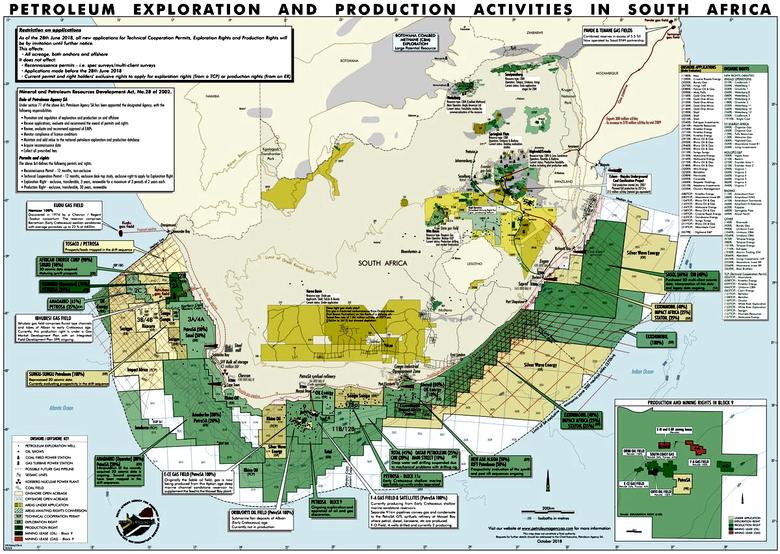

PE - 31 January 2020 - The South African government published its long-anticipated draft oil and gas legislation on Christmas Eve, hoping it will usher in a new era of exploration and production. To combat the country's energy deficit, it must pave the way for the rapid development of substantial recent discoveries, including Total's huge Brulpadda field last February, and prospects.

The domestic economy provides marketing potential to a range of potential industrial offtakers as well as new gas-to-power projects. Challenging offshore conditions, transportation to market issues, the global glut and historically low prices of gas—as well as the financial woes of potential anchor customer Eskom—dull the outlook.

It is also another example of the global conundrum for governments of resource-blessed countries seeking to maximising revenue while still securing investment. The question is whether the terms are attractive enough when nations are competing increasingly aggressively for investment from international oil companies (IOCs) and the potential demand destruction from the energy transition looms over the coming decades. The attractiveness of South Africa's terms will have ramifications far beyond its borders.

Unlocking the code

The draft legislation has two major factors that could potentially be a barrier to investment: a 20pc interest for a state-owned partner who will be carried up to the production stage and a 10pc participating interest for broad-based black economic empowerment (B-BBEE) companies. The Department of Mineral Resources and Energy also plans to create a petroleum agency and will consult on all the reforms until 21 February.

The draft code "is a success" in that it provides a legislative framework for South Africa's nascent oil and gas industry, says Juma Mlawa, a sub-Saharan Africa analyst at consultancy Wood Mackenzie. "However, IOCs will be concerned with the 20pc carried interest and the 10pc reserved for B-BBEE companies. The terms will put South Africa in the top 10 of mandatory participation requirements globally."

The 10pc reservation is not actually a new policy. For example, there is 10pc B-BBEE equity in block 11B/12B, where Total's 500mn bl oe gas-condensate Brulpadda discovery is located. The partners financed Main Street 1549 Proprietary's share of exploration costs in 2019. "We think the 10pc B-BBEE stake may slow down investment, particularly in acreage held by smaller independents. But with regard to equity held by the majors, we do not think it will be a showstopper given the promise that South Africa's geology presents," says Mlawa.

Carried interest through exploration and appraisal is common including in other jurisdictions that operate under a tax and royalty regime. "However, it is important for the government to pay its way through development and production, rather than reimburse costs at the point of commencing development, in order to mitigate against the risk of the government paying for fields that are uneconomic to produce," says Mitun Patel, energy consultant at QED Consulting.

He adds that the 20pc state-owned stake should not necessarily be thought about in a security of supply context. "The South African government should already have sufficient power to dictate that domestic supply has priority over exports, subject to market economics."

"The 10pc black representation will encourage joint ventures with South African B-BBEE owned companies and develop local South African upstream capabilities. It must, however, be understood that domestic capital requirements will be significant, whether B-BBEE or not. Any possible capital deficiencies should not be an impediment to the development of an opportunity," Patel warns.

Overall, though, he views the draft law as "acceptable, with no major issues". IOCs, generally, will value more highly concessions based on the potential to discover large reserves, proximity to market, with acceptable prices, low costs and in regions with good security. "The government should offer low and stable taxation and other pro-investment laws—the result will be more exploration and production and improved security of supply."

Preparing for Brulpadda

Brulpadda—which, with an estimated c.2.8-5.5tn ft³ of gas initially in place, could meet South Africa's existing demand for many years—should be the jewel-in-the-crown of South Africa's production over the next decades. But, while it shows immense promise, there are several milestones to pass before it reaches FID.

The priority for 2020 is a further exploration campaign, which could include up to three wells drilled. This means the appraisal stage will not happen until 2021, Mlawa expects. "Once Total and its partners get more clarity on the resource base, they will be better placed to ascertain the development plan for Block 11B/12B. FID won't be until late 2021 at the earliest."

Patel agrees that FID will be subject to the outcome of additional exploration drilling but adds that it "will need an anchor load to make economic sense". What South Africa has in its favour, unlike most of sub-Saharan Africa, is a ready market for gas. One ready source of demand is the country's power sector, where several power stations are running on imported fuel oil and diesel.

South Africa also pioneered the gas-to-liquids (GTL) industry but the fields that underpin its supply are in decline. There is scope for Brulpadda to supply Mossel Bay GTL in the near term and, longer term, other large industrial end-users.

Transportation issues

The issue will be getting the gas to market. Gauteng—where 80pc of the demand is located—is over 1000km away and thus unlikely to be economically attractive to supply, according to Patel. Major population and industrial centres Cape Town, Saldanha and Port Elizabeth, with existing oil-fired power plants and plans for new gas-fired power plants, are also more than 300km away.

"With the demand mainly from the GTL plant and the Gourikwa power plant there may not be sufficient market volumes with high enough value in Mossel Bay itself," says Patel. "Therefore, Total may be looking to additional demand, for example the new gas-fired plants being planned by 2027, in the area or nearby."

South Africa has a small but well-established gas market that is hungry for both more volumes and supply diversity, so small-scale LNG could be an option. "The challenge comes when a new anchor load project such as a large 1000MW power plant is required to help underpin the investment in [larger] infrastructure," says Patel.

"South Africa has a large power demand that is currently undersupplied. However, the credit risk presented by sales to a single buyer such as Eskom is a major challenge. Unbundling Eskom and opening the power market to competition will take many years. Until then, restructuring Eskom's debt will be key."

International competition

South Africa is also competing for necessary investment in a challenging global market. Lower oil and gas prices combined with a focus on capital disciple mean host governments are being forced to consider offering better terms to attract IOCs.

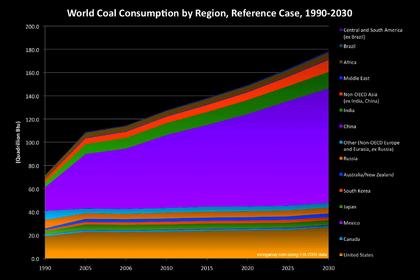

"The general sentiment is that governments in sub-Saharan Africa have to offer better terms to incentivise investment," says Mlawa. The region has been severely impacted by capital flight since 2014 and investment is 40pc lower than "the heady days of $100/bl when [a nominal] $51bn was invested," he says. "Gas, particularly deepwater, presents further development challenges given the lack of a domestic market in most countries."

Governments across sub-Saharan Africa are realising that the balance of power in negotiations has shifted more in IOCs' favour: Gabon is an example of the trend "It revised its terms last year and included improved terms for gas—lower royalties and profit shares—that could unlock stranded potential," Mlawa notes.

Current taxes and royalties make South Africa a favourable destination for investment, according to Mlawa. "We have seen this bear fruit in the past decade with the majors acquiring acreage offshore. The onus is for the geology to deliver. Brulpadda de-risked the geology of the Paddavise Fairway but there is still more work required in de-risking geology further east offshore Durban and further west in the Orange basin."

However, South Africa is not a mature E&P province and there have not been many major discoveries. "This may result in higher costs," says Patel. And the draft hydrocarbon bill hasn't addressed fiscal terms. "We understand that there is a piece of legislation expected this year that will address royalties and taxes applicable to oil and gas companies," says Mlawa.

-----

Earlier: