CHANGES IN RUSSIA'S STRATEGY

By Sebastian Kennedy Founding Editor Energy Flux (newsletter)

ENERGYCENTRAL - European policies on climate emissions and clean energy are reshaping the balance of power between the EU and one of its main external energy suppliers: Russia.

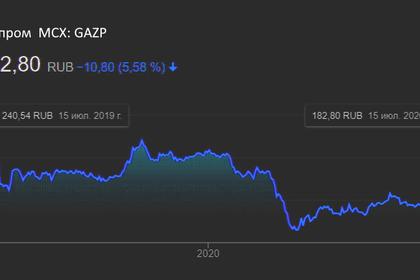

Europe’s headlong rush to replace natural gas with clean hydrogen has prompted a strategic rethink at Gazprom, Russia’s state gas company that holds the monopoly over Russian pipeline gas exports. While forcing Russia’s hand is a triumph of EU climate leadership, Europe will need to develop alternative non-Russian sources in tandem to ensure Gazprom does not corner what is hoped to be a growing market for hydrogen supply.

The co-dependency between the EU and Russia around natural gas has long divided opinion across European capitals. While the old debate rages on, the next frontier is opening up: the race for market share to supply low- or zero-emissions hydrogen to the bloc.

Not for the first time, Europe is embarking on a quest for the Holy Grail of decarbonisation: a green hydrogen-based economy that pushes unabated natural gas out of the market. In response, Russia is embracing hydrogen to maintain Gazprom’s sales volumes. Kremlin officials by their own admission see this as both a threat and opportunity.

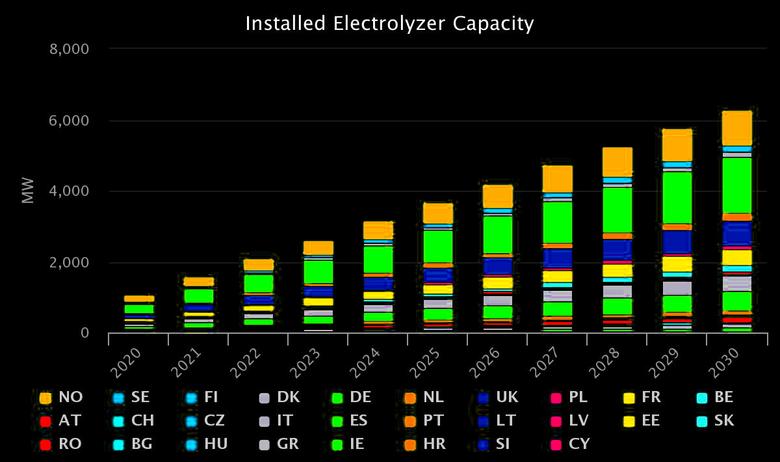

The European Commission’s proposed new hydrogen strategy calls for 40 gigawatts (GW) of European green hydrogen production capacity to be installed by 2030, and another 40 GW “in Europe’s neighbourhood with export to the EU”.

That’s an almighty undertaking. Spain’s Iberdrola will next year bring online Europe’s largest dedicated green hydrogen production facility for industrial application in Puertollano, with a rated capacity of 20 MW. To achieve only the within-EU 2030 target, Europe would need to build around 200 such facilities every year for the next decade.

To help deliver the other 40 GW, the EC is seeking to put hydrogen on the EU’s international diplomatic agenda. Brussels hopes to kick-start development of huge North African solar farms equipped with arrays of electrolysers to produce vast quantities of green hydrogen. This initiative might well bear some fruit; but reaching tens of gigawatts with associated H2 supply infrastructure within a decade is less certain.

Transporting hydrogen over long distances comes with myriad technical and economic challenges. Hydrogen can be liquefied or bound in bigger molecules that are easier to transport (e.g. ammonia), but widespread global trade of hydrogen aboard ocean-going tankers is not a realistic commercial proposition this side of 2030. Even if intercontinental trade does take off, waterborne hydrogen will command a premium to cover transportation costs.

It is more straightforward and cost-effective to allow existing natural gas pipelines to carry a small percentage of hydrogen in the methane stream, but the EC is not keen on so-called ‘blending’. If each member state has a different proportion flowing in its pipes this would fragment the internal gas market and undermine security of supply, which can cause price spikes in times of scarcity.

Hydrogen production will therefore be developed initially in industrial clusters close to end-users, as is the plan in Puertollano where an adjacent fertiliser plant will absorb all the volumes. As hydrogen demand increases, larger volumes will be piped as pure H2 over longer distances in new or adapted pipes and across wider hydrogen networks.

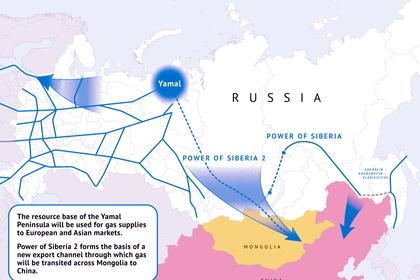

Moscow saw all this coming a mile off. Gazprom’s Nord Stream 2 (NS2) gas pipeline project, which is nearly complete and would already be in operation today had US sanctions not scared off a Swiss offshore pipelaying contractor late last year, has been future-proofed to carry pure hydrogen, if needed. The existing Nord Stream 1 pipeline running beneath the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany could also carry around 80% hydrogen, according to Gazprom.

NS2 will probably be completed some time next year, despite Washington’s best efforts to kill it off. When operational, Russia will have the infrastructure in place to deliver a large chunk of the hydrogen called for in the EC’s own strategy. The next challenge will be to produce large volumes of hydrogen cost effectively in Russia.

Gazprom has been exploring production techniques for several years now. Until recently, the Kremlin saw Russia’s vast domestic natural gas reserves as convenient feedstock to produce either ‘blue’ hydrogen using carbon capture (CCS) technology, or ‘turquoise’ hydrogen formed via pyrolysis with CCS.

Last month, Russia’s ministry of energy changed tack by launching an initiative for Gazprom to team up with state nuclear company Rosatom to produce ‘green’ hydrogen using nuclear powered electrolysers.

This seems to be a tacit acknowledgment from Moscow of two things: one, that Europe sees only a limited role for blue hydrogen as a stepping-stone towards the 100% zero emissions green alternative; and two, that if CCS technology fails to commercialise as many predict, Russian gas will effectively be barred from EU markets—potentially stranding Russian pipelines such as Nord Stream 1 and 2.

The EC’s H2 strategy confirms that policymakers in Brussels are wary of over-reliance on blue hydrogen, as this would lock Europe into investing in fossil fuel and CCS infrastructure that is quickly rendered redundant. Infrastructure owners would more than likely lobby to prolong asset life, so shifting from blue to green hydrogen could end up being as difficult and slow as shifting from coal to unabated gas in power generation—something that should have happened decades ago but is only today starting to happen meaningfully across Europe.

It is not yet commercially viable to produce large volumes of green, blue or turquoise hydrogen without some form of subsidy, and if anything Russia is hedging its bets on how Europe’s latest hydrogen odyssey will pan out. But the bottom line is this: Gazprom is well-placed to succeed in ramping up some form of hydrogen exports to meet European demand, should it materialise. If other sources do not keep up, EU leaders will have to sell the politically awkward narrative that augmenting Russian market power is a necessary part of decarbonising European economies.

-----

This thought leadership article was originally shared with Energy Central's Energy Collective Group. The communities are a place where professionals in the power industry can share, learn and connect in a collaborative environment. Join the Energy Collective Group today and learn from others who work in the industry.

-----

Earlier: