U.S. LNG INCREASE

By SEB KENNEDY Founding Editor Energy Flux newsletter

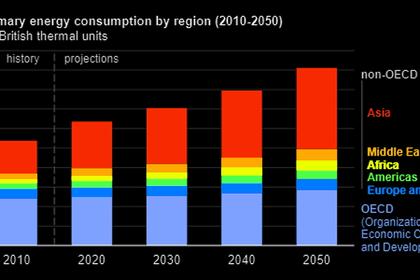

ENERGYCENTRAL - Nov 1, 2021 - Cheap, abundant natural gas has become the bedrock of the American economy – but the drillers that produce it are sitting on their hands, even as prices rise. Manufacturers are getting twitchy, calling for liquefied natural gas exports to be capped. This is unlikely for many reasons, meaning US consumers might have to get used to higher bills. This could be good news for both coal and renewables – unless jaded investors forgive the US shale sector’s sins. In any case, the US isn’t quite ready to keep its gas for itself.

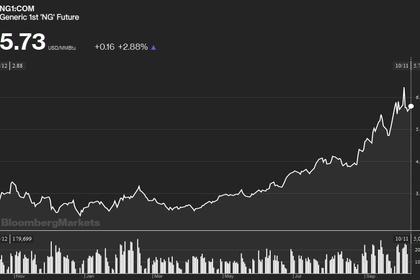

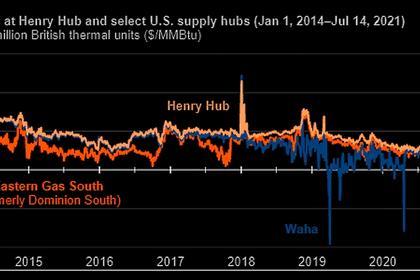

Liquefied natural gas is giving America a taste of the true value of a precious energy resource that it has for too long squandered at the wellhead. Surging US LNG exports jacked up prices to levels not seen since the fracking boom flooded the domestic market with cheap gas in the early 2010s.

Futures on US gas benchmark Henry Hub are trading at more than $6 per million British thermal units (MMBtu) for delivery in December and January. That’s more than double the year-ago price and triple the long-run assumption built into many energy analysts’ cost models. S&P Platts is forecasting it could hit $12-14/MMBtu this winter.

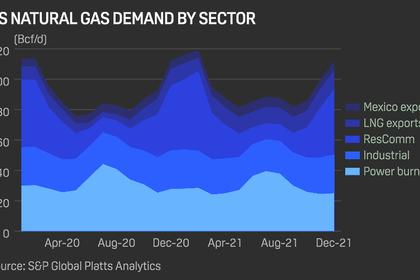

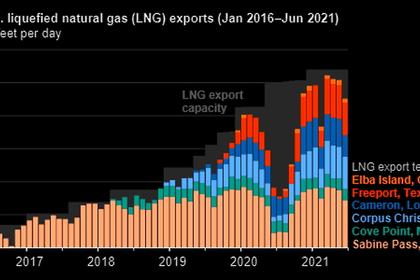

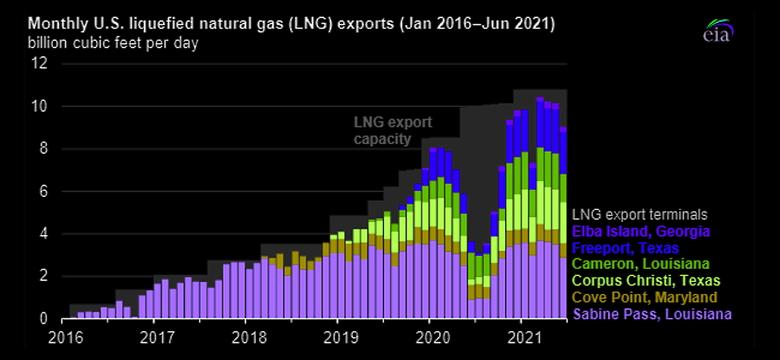

This would not be happening if US gas stayed within the country’s borders. America rose swiftly from a standing start in 2015 to become the world’s third largest LNG exporter behind Australia and Qatar, and is projected to occupy the top spot by mid-decade.

Despite a brief Covid-related output dip, US LNG exports rose 31% in 2020 to hit an all-time high of 2.4 trillion cubic feet (Tcf). This equates to roughly 7% of US gas production. On top of that, another 6% is exported to Mexico and 2.7% to Canada by pipeline.

Meaty margins

The proliferation of liquefaction plants along the US Gulf Coast and eastern seaboard has linked gas-rich North America with gas-starved global markets. As the post-lockdown recovery pushes gas prices to crisis levels in Europe and Asia, US LNG plants are selling cargoes at premiums that their investors probably never imagined in their wildest dreams.

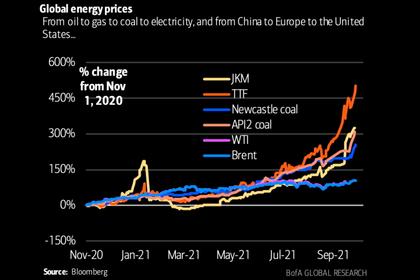

American natural gas prices have risen much less than in Europe and Asia, so the profit margins for shipping US LNG overseas are today gargantuan even though the cost of production has ballooned. Dutch TTF gas futures are trading at more than $30/MMBtu over the winter months, while Asian LNG JKM futures peak at $34/MMBtu.

Assuming a shipping cost of $120,000 per day and a liquefaction tolling fee of $2.80/MMBtu, a cargo of American LNG arriving in Asia this December will netback ~$21.64/MMBtu if sold on the spot market. For a standard vessel carrying 165,000 cubic metres of LNG, that equates to roughly $81 million of profit*.

Little wonder, then, that US LNG plants are operating at or near full capacity. This is quite a turnaround from mid-2020, when many of these same facilities throttled back output. The first wave of lockdowns hammered global energy demand, leaving a massive glut that crashed prices in key LNG export markets below the cost of production.

* Assumes 1,020 Btu per cubic feet of feed gas in Louisiana and Texas (EIA)

Manufacturers wince

Today the global economic recovery is straining against the limits of existing energy supply, pushing up fuel prices across the board. This has startled energy-intensive American industries, which are not used to paying $6/MMBtu for their gas.

The Industrial Energy Consumers of America last month fired a warning shot at the White House, calling for LNG exports to be curbed “to prevent a supply crisis” this winter.

IECA president & CEO Paul Cicio told Energy Flux there’s a strong correlation between expensive gas and job losses. His members are concerned that LNG exports could herald a return to the pre-shale days:

“For the US manufacturing sector, natural gas ‘delivered’ prices increased 209% from 1999 to 2008, or 23% a year, to an average price of $9.50 per MMBtu in 2008. Manufacturing employment fell from 17 million to 13.5 million [in this period].”

The IECA argues that the Natural Gas Act gives the Department of Energy powers to limit or deny exports to countries that do not have a free trade agreement with the US. Cicio said these destinations account for most US LNG exports and are:

“the same countries that often create barriers to the importation of US manufactured goods… Exports must continuously be in the public interest. [If not], the DOE has the ability to [withdraw] authorization to export. The secretary has the obligation to ensure to the American people that any specific export approval remains in the public interest.”

(Geo)political blunder

The definition of ‘public interest’ is much wider than the bottom line of manufacturers – even if these companies employ millions of people. LNG has taken on a geopolitical significance and curtailing it would undermine US foreign policy objectives.

For a start, it would send an inconsistent message to Europe about the availability of American ‘freedom gas’ as a bulwark against dependence on Russia. Also, US companies are busy developing LNG import terminals in Vietnam and elsewhere in Asia to provide an outlet for American fracked gas. These projects are often part of a wider diplomatic effort to bolster US trade relations with countries in China’s regional orbit.

“Lots of US allies depend on US LNG,” says Nikos Tsafos, the James R. Schlesinger chair in energy and geopolitics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He told Energy Flux:

“The United States is a big player now, and it’s hard to cut back exports without causing a major disruption in the market… I don’t see a big push for administration action to curtail exports right now. The conversation is definitely starting, but it’s not mature yet… For now, how much the United States exports is largely a question left to markets.”

As regular Energy Flux readers will be aware, the energy crunch has brought Chinese state oil giants back to the table to negotiate long-term LNG purchases from US exporters. A move to curb output now would scupper the Biden administration’s efforts to thaw the Trump-era trade war with Beijing. President Joe Biden needs a big geopolitical victory ahead of tight 2022 midterm elections.

Securing more long-term export deals would be a domestic political win too, although not universally within Democratic caucuses. Donald Trump wanted LNG to play a big role in addressing the US trade deficit with China. Biden could win over centrist voters in gas-producing swing states such as Pennsylvania and Virginia by claiming he made that happen.

It would also go down well in Republican-voting oil and gas mecca Texas, where Democrats last year secured their largest share of the presidential vote in 45 years. The political calculus might be that turning Texas blue would be worth losing a few anti-fossil fuel votes in Democrat strongholds.

Capping LNG exports would have major market repercussions. It would certainly crash domestic gas prices, but at the expense of investment in US upstream production – particularly for ‘dry’ gas wells that don’t also produce oil.

This would build up problems down the line. North America would rely more on associated gas from oil wells, which ramp up and down depending on the oil price, not gas demand. This creates supply-demand mismatches that stoke price volatility. Manufacturers probably wouldn’t appreciate that too much either.

Equally unconscionable is for America to follow Australia down the tortured path of domestic gas supply obligations or, even more absurdly, simultaneously importing and exporting LNG. The market will ultimately find a way to keep shale gas flowing into liquefaction plants and out into the global LNG market.

Prodding the shale corpse

US oil and gas production is rising in response to higher prices, but only sluggishly. US crude benchmark WTI this week hit a nine-year high of $84/barrel, marking a 36% surge since August. In ‘normal’ times this rally would drive huge associated gas production from oil-rich shale plays such as the Eagle Ford and Permian basins in Texas and New Mexico – with correspondingly vast increases in gas flaring.

Instead, we are seeing drilling activity lagging the oil price recovery. Even in the Powder River Basin, a play rich in coalbed methane where the rig count is recovering, activity remains far below pre-pandemic levels:

This also reflected in gas flaring rates, which appear to have picked up in Q1 and Q2 this year but remain below 2020 levels. Mark Davis, CEO of flare capture specialist Capterio, said flaring is “structurally lower” compared to 2020 and 2019 due to the relative “decline in rig counts and start-up of new midstream capacity”.

The US – for years the global swing producer – seems to be entering a period of supply inelasticity. Since the US accounted for the vast majority of oil supply growth over the last decade and is by some margin the world’s biggest gas producer, this is hugely significant for global energy markets.

Inelasticity is partly explained by American oil and gas producers hedging their positions for the winter, meaning they won’t benefit much from rising prices in the coming months. Only if Henry Hub remains elevated through 2022 will those prices stimulate more drilling. Labour shortages and rising equipment costs are also weighing on activity.

The epic events of 2020 cast a long shadow. The heavily indebted US shale patch is still shell-shocked from the Covid-induced Russia-Saudi oil price war. Rather than reinvesting in new wells, boards are (belatedly) paying down debt and returning cash to long-suffering investors.

Today, the biggest constraint is money. Fracking has been a ruinous enterprise for Wall Street. Those that financed the shale boom have very little to show for it, as profits were offset by the never-ending need to drill new wells to offset declines.

This was compounded by governance issues. Greedy shale bosses with no skin in the game paid themselves lavish salaries and bonuses while leveraging up their shale companies with unsustainable amounts of debt. Complicit boards stood by and watched as shareholder value was systematically destroyed and executives took off in golden parachutes.

New York private equity firm Kimmeridge describes the shale industry’s prioritisation of growth over returns as a “failed business model”. The Covid oil crash, which briefly turned WTI negative, gave “a real-time look at how [un]willing Boards were to hold management teams accountable”.

“It became clear which Boards were … focused on ensuring their executives were still rewarded as their share prices collapsed. As the sector continues to struggle with re-establishing investor credibility, we believe overhauling executive compensation plans is the key to accelerating a change of perception.” – Kimmeridge

Coal and renewables wait in the wings

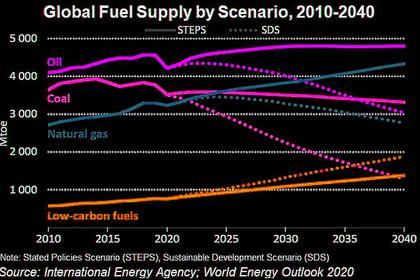

This critique implies a cultural reticence to reforms that could stymie investment for the foreseeable future. If this endures and US hydrocarbon production flatlines against a backdrop of rising LNG exports, structurally higher gas prices would prevail – favouring both dirty and clean alternatives.

Nikos Tsafos of the CSIS said higher gas prices might prolong the decline of coal-fired generation while simultaneously benefitting renewables:

“They also make it easier to justify hydrogen and building electrification. In fact, from the perspective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, cheap gas is a problem because it’s hard to dislodge. Higher prices make alternatives more attractive.”

Looking further out, Tsafos says it is possible that the emissions argument might eventually provide political cover for a future decision to curtail American LNG exports:

“But I hope this is part of a thoughtful strategy about how to align U.S. hydrocarbon production with the imperatives of the energy transition, not flipping a switch as a way to achieve climate goals.”

Yet this scenario may not arise at all in any meaningful timeframe. Ben Schlesinger of Maryland-based natural gas consultancy BSA Energy said the political and economic fundamentals for US LNG remain strong:

“There’s a market out there for capital, there’s plenty of gas and plenty of demand. There’s also plenty of coal to be replaced in Asia.”

Schlesinger told Energy Flux the market will do its thing. Strong LNG exports and high prices are, perhaps counterintuitively, vital to continued upstream investment, he added:

“If we don’t export, we will run out of gas. We will simply stop producing and leave it in the ground. But I don’t think we will run out of gas, nor will we stop drilling.”

Polemicists muster at COP26

‘Leave it in the ground’ has become a clarion call for climate activists, and this message will get plenty of airtime at COP26. The global energy crunch arrived just in time to give extra weight to the gas and LNG industry’s age-old counter-argument: ‘You need us’.

This is undoubtedly true. But for how long? The polemical role of gas in the energy transition hinges squarely on how quickly world leaders agree to decarbonise their economies – and the cost-benefit analysis of cleaner alternatives.

In the meantime, the global gas crunch is showing signs of abating. Dutch TTF gas futures fell as much as 8% yesterday after Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered Gazprom to start refilling the company’s storage facilities in Austria and Germany as soon as domestic stocks are full. Even though no more gas has arrived in Europe (and some experts doubt Russia’s ability to deliver quickly), this pulled Henry Hub down as much as 5% on Thursday.

The forward curve has always suggested US gas market tightness will quickly subside. The May 2022 Henry Hub contract is trading at $4.12/MMBtu – a third below the November 2021 price. Much will depend on the severity of the coming winter.

In all likelihood, America’s experience of the global energy crisis will be much less brutal than that of Europe or Asia thanks to the country’s strong gas production base. LNG exports bring exposure to global market forces, but these same forces will coax more molecules out of the ground for as long as the economic calculus justifies it.

The price shock could jolt manufacturers into managing price risk exposure more effectively. On the eve of COP26, it may also remind the White House of the importance of gas and LNG to American interests at home and abroad.

Don’t be surprised if the US delegation in Glasgow goes no further than supporting the industry’s own tepid targets to clean up its huge methane and flaring footprint. COP26 noise might create the illusion that the Overton window is shifting on fossil fuels, but make no mistake: the US is about as likely to ‘keep American gas for Americans’ as it is to ‘leave it in the ground’.

-----

This thought leadership article was originally shared with Energy Central's Energy Collective Group. The communities are a place where professionals in the power industry can share, learn and connect in a collaborative environment. Join the Energy Collective Group today and learn from others who work in the industry.

-----

Earlier: