GREEN EUROPEAN DEAL

By Peter Poptchev Ambassador (Ret.) NET ZERO Foundation International Climate Network

ENERGYCENTRAL - Mar 23, 2021 - Extending the operational geographic scope of the European Green Deal

In its December 2019 Communication on the European Green Deal (COM (2019) 640 final) the European Commission pledged to put an emphasis on supporting not just the EU Member States but immediate neighbours as well. The ecological transition for Europe can only be fully effective, the Commission said, if the EU’s immediate neighbourhood also takes effective action. Work is underway on a green agenda for the Western Balkans, it added. The Commission and the High Representative are also envisaging, the Communication continued, a number of strong environment, energy and climate partnerships with the Southern Neighbourhood and within the Eastern Partnership. While the message is resolute enough the intended energy and climate transition, bearing important geopolitical connotations, has not matured much even on the conceptual level. This article aims to stimulate debate and action on the issue.

Energy and climate policy, supply security and long-haul trans-border energy infrastructure have for many years been of substantial common interest between the EU and the Eastern Partnership and the Southern Neighbourhood countries, albeit with slight variations in purpose and content. With the adoption of the European Green Deal, acceptance thereof by leading economies and energy majors, and the global leadership role the EU has assumed in the Planet’s advent to climate neutrality by 2050 the task of including in this transformative process immediate neighbours lying to Europe’s East and South cannot be overlooked further.

So far as the Eastern dimension is concerned, the design includes six Western Balkan countries - Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo*, Montenegro, Republic of North Macedonia, and Serbia – as well as Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, which are three of the members of the Eastern Partnership. While the list is open, it is these nine Contracting Parties to the Energy Community that seem to elicit a moderate expectation that they are politically and operationally attached to the long-term European Green Deal strategy. Without a legal obligation to do so, many of them, states the 2020 Energy Community Implementation Report, are currently also engaging in drafting integrated energy and climate plans in line with the Governance Regulation of the EU Clean Energy Package.

The enabling role of the EU Member States

While the European Commission and other EU institutions will be expected to provide strategic guidance and support, including financing, to “neighbourgood” schemes and projects, it is the EU member states, their governments, companies and academics that could actually engage in EGD-related cooperation with Western Balkan and several Eastern Partnership countries. These potentially willing EU member states fall into two relative categories. The first one lists twelve member states in Central and South Eastern Europe - Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Greece, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. Some of them are skeptical about their own capacity to fulfill the 55% reduction of GHG gases by 2030 either because of a painful process of phasing out coal/lignite as an energy source or a heightened apprehension that this abrupt transition would hurt their competitive advantages in the industrial, transportation, construction, agricultural and other sectors. Most national integrated energy and climate plans in this group are less ambitious than the European Commission would have liked. The 12 EU member states would therefore need to put their own EGD act together, and gain confidence and assurances that this will be a real and tangible growth and jobs strategy, before they venture open-border energy and climate projects in the region. It is their common interest to initiate as soon as possible in-depth consultations with the EU Commission and among themselves on, firstly, what EU-approved joint cross-border projects they could undertake in the next 5 – 10 years, and, secondly, what would be the modalities for such EGD-based regional projects to be profitably extended to their neighbours in the Western Balkans as well as Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia. Admittedly, the EU Commission has not yet managed to share with the Member States in sufficient detail its interpretation and guidance on implementing important EGD sectoral strategies.

The second category of EU member states should comprise EGD “front-runners” such as Germany, France, the Netherlands, Denmark, etc. and any other member state or professional association willing to commit to the daunting task of supporting their Eastern partners in effectively implementing EGD benchmarks. There should be a system of incentivizing companies and R&D centres to cooperate with peers in EU Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe, including Energy Community Contracting Parties. International and local private capital, compliant with “green financing” and Green Taxonomy rules, should be invited to join forces. This would open up opportunities for commercial and financial interests from outside the EU – the U.S., UK, Japan, ROK, etc. – to also approach what will be an expanding market.

What makes the wider region potentially contributive to the European Green Deal

It would be politically naïve to expect that a profound EGD-related cooperation between mature EU economies and their Energy Community neighbours would materialize based on common declaratory commitments to climate neutrality. The EGD strategy, in its developed sectoral dimensions, including a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and a revised Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is about a hard-core, disruptive, transition covering energy, industry, construction, agriculture and forestry, water management, circular economy schemes, etc. The transition prospects for each of the nine Contracting Parties will be determined by both its national ambition and regulatory compliance with the EGD acquis, and its potential to contribute, individually and jointly, to the resource and production base of the new decarbonized European economy. A sub-regional and regional approach will probably emerge as the viable business principle capable of achieving the necessary scaling up and optimal operational frameworks.

From a regional perspective some of the comparative advantages of Central and South East Europe worth mentioning - not in order of importance – are: renewables, both solar and wind; blue and in particular green (clean) hydrogen; regenerative agriculture; and a substantial industrial and manufacturing potential in most EU member states in the region, including Ukraine. These capabilities, including software development and digital solutions, can be reoriented towards innovation and production of machinery and equipment that would service the energy efficiency, e-transportation, battery, distributed energy and climate mitigation needs of the countries in the wider region.

For the purpose of this article the potential of CSEE for renewables and (clean) hydrogen is taken as an example. The choice is intentional because if the case for a substantial renewables and hydrogen potential of this region can be substantiated, important long-term transformative choices and consequences would follow for both the regional countries and the EU at large.

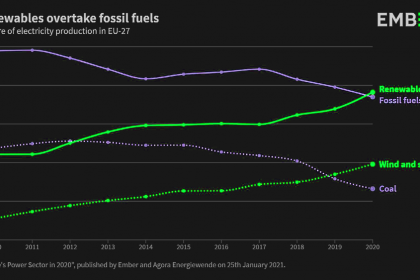

The full deployment of renewable options identified in a 2020 IRENA (International Renewable Energy Agency) study could raise the 2030 renewables share to 34%, cost-effectively, for the whole CESEC region (most regional EU Member States plus eight Contracting Parties, including Ukraine and Moldova), compared to 24% in the Reference Case. For CESEC’s eight Contracting Parties of the Energy Community alone, a “RE map scenario” could boost renewables to 30% by 2030, compared to 19% in the Reference Case.

In the so-called RE map Case, renewable power capacity grows from 109 GW in 2015 to 265 GW in 2030. This includes 116 GW of solar photovoltaic (PV), 58 GW of wind, 67 GW of hydro and 22 GW of biomass power. With the appropriate policies in place, about 55% of the electricity consumed by CESEC members could come from renewable sources (around 620 TWh of renewable power generation in 2030, compared to 253 TWh in 2015. In other words the regional renewables potential is twice bigger than presently envisaged.

The above IRENA quotes do not take into account the recently established immense natural potential for offshore wind (bottom-fixed and floating) and the localised potential for wave energy in the seas surrounding Central and South East Europe: the Baltic, the Adriatic, the Mediterranean, the Aegean and the Black Sea. New technical solutions for solar power on the sea surface are also being developed. The EU Commission will facilitate cross-border cooperation and encourage Member States to integrate objectives of offshore renewable energy development in their national maritime spatial plans, in line with national energy and climate plans. A new approach to offshore renewable energy and grid infrastructure is being introduced, where the spatial planning of offshore renewable energy is closely linked with offshore and onshore grid development, establishing what measures would support the infrastructure needed to make large-scale offshore renewable energy a reality.

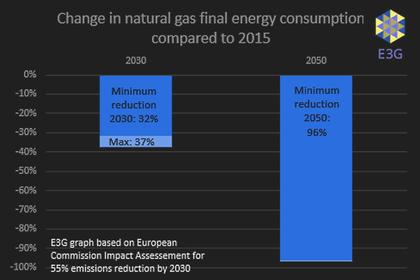

Based on this substantial renewables potential, Central and South East Europe, including the Western Balkans countries, Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, can develop as a sizeable component of the future European Hydrogen Eco-system - alongside Italy, Portugal and Spain for solar and North-West Europe for wind power. However, hydrogen is presently grossly underestimated in the national integrated energy and climate plans of most EU member states in CSEE, and the situation is even worse in the plans of the Energy Community Contracting Parties. This state of affairs can be easily remedied with the inclusion of both the EU Member States and the Contracting Parties in structured regional cooperation on promoting green hydrogen. Starting with a review of the existing region-wide industrial value chain and setting parameters for boosting demand for green hydrogen, i.e. industrial applications and mobility technologies, the aim will be to develop a viable regional scheme of producing, transmitting, compressing and storing green hydrogen, including the promotion of research and innovation. Once such a regional green hydrogen-geared scheme begins to take shape it will by itself evoke the necessary supportive framework and demand better functioning of the regional energy markets, establish clear regulatory rules (the EU Commission actually provided the blueprint of hydrogen networks regulation in February 2021), and review the needs for upgrading existing (gas) pipelines and building new dedicated infrastructure. The European Clean Hydrogen Alliance, an ideal transmission of hydrogen knowledge and technologies all over Europe, could share with the CSEE countries its access to robust channels of investments. Notably, the ‘Next Generation EU’ instrument highlights hydrogen as an investment priority to boost economic growth and resilience, create local jobs and (!) consolidate the EU’s global leadership. Europe will secure cooperation opportunities with neighboring countries and regions of the EU and work to establish a global hydrogen market.

South East Europe in particular could assist in realizing EU’s ambition to establish and be a leader in a global hydrogen market by linking its own potential for clean hydrogen with this of North Africa, i.e. Egypt (Prof. Dr. Ad van Wijk). It is reasonable to expect that competition between the EU and China, and others such as Japan and ROK, might eventually lead to green hydrogen becoming an internationally traded commodity, very much like crude is today. It will probably take 10 years for CSEE to become a leading factor of green hydrogen. Given the historically slow pace of cross-border cooperation in this region, the setting up of the political, economic, industrial, and financial frameworks of a future regional green hydrogen market should start now.

The game-changing impact of EGD’s sectoral strategies and transformative legislation

Various forms of political and economic cooperation in Central and South East Europe, including the Eastern Partnership, have been explored before, with mostly humble outcomes. Two latest formats targeting regional energy cooperation – CESEC and the Three Seas Initiative – advanced important EU policies and concepts but still leave much to be desired. It is not of course easy to pool the political will and the resources of over 20 countries, twelve of them EU Member States, featuring rather diverse sizes of territory, population, economy, energy sector, GDP, and business climate. What however creates a totally new context is the strategic vision, financial support and technology adoption opportunities offered by the European Green Deal. The actual game changer in this context is the across-the-board embrace of the Green Transition and the far-reaching potential of the Energy System Integration Strategy with its three principles: circularity; direct electrification where possible; and promotion of green fuels, scaling up green hydrogen above all. It is not just the geographic proximity of the two dozen or so countries concerned but, rather, the qualitatively different design of the more efficient integrated energy system, requiring open borders, better interconnectivity and decentralized forms of delivery and transmission of energy that creates a new enabling framework for broad regional cooperation. The principle of open borders and integrated energy system will link the CSEE region to attractive markets such as Italy, Austria and Germany, and further on to Western Europe, in other words it will open up the whole European single market.

With opportunities often come challenges. Companies in Central and South East Europe – in energy and all other EGD-relevant sectors – will probably find it difficult to develop their technical and technology adoption capabilities to a level, allowing them to apply effectively and in a coordinated manner the New Industrial Strategy, the Hydrogen Strategy, and in particular the Energy System Integration Strategy. Presently, this escapes even many energy and industrial companies in Western Europe, let alone their peers in CSEE. A new green economic thinking and a competitive corporate culture will have to be bred in CSEE, which should seek intra-European and international, again U.S., UK, Japan, ROK, forms of research and innovation, business clustering, both nationally and regionally, opening of joint experimentation sites, and exchanging theoretical and practical knowledge on new industrial processes and products. A massive influx of digitalization schemes, AI and ML solutions, grid response and grid harmonization software, cloud and IoT technologies – all of these innovations should be gradually introduced in the integrated regional energy market. These are the attributes of decentralized and distributed energy models which CSEE, including Contracting Parties, has to adopt if the region wants to be part and parcel of the European and global transition to climate neutrality. In addition, CSEE will profit substantially from consistent energy efficiency measures, which, on the national level, should precede or at least go simultaneously with all other EGD policies.

In spite of past failures the Energy Community assures us that “the signs are looking good”: after many years of negotiations, the amendments to the Energy Community Treaty will finally be sealed at the end of 2021, which is expected to enhance compliance with the acquis by the Contracting Parties and at the same time unlock the potential for market integration between the European Union and the Western Balkans. Ukraine has been commended by the Energy Community for its consistent contribution. The European Union’s interest in phasing out coal, pricing carbon and extending the “renovation wave” for non-efficient buildings also in its immediate Neighbourhood is increasing, states the EC Implementation Report.

Conclusion

It is obvious that Central and South East Europe, including immediate neighbours, needs special attention by both the European institutions, including in particular the European Investment Bank (IEB), international organisations such as the World Bank and IMF as well as private capital. Strategic guidance should be offered and applied by the European Commission on a priority basis. The geopolitical importance of these measures cannot be overstated. The European Green Deal is an ideal platform for initiating daring sectoral and regional projects which should take the regional countries to a higher technological orbit and new wealth. This undertaking needs reliable governments, consistent national and EU regulators, visionary entrepreneurs and financiers, talented engineers, and parliamentary and civil society oversight.

-----

This thought leadership article was originally shared with Energy Central's Clean Power Community Group. The communities are a place where professionals in the power industry can share, learn and connect in a collaborative environment. Join the Clean Power Community today and learn from others who work in the industry.

-----

Earlier: