EUROPEAN ENERGY STORM

BLOOMBERG - 16 MAY 2022 - A gathering storm of renewed energy price-spikes, surging food costs and corresponding social and economic dangers is focusing the minds of Brussels officials who worry of multiple shocks cascading through the European Union from Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Viewed from the Berlaymont headquarters and nearby buildings that house the European Commission in the Belgian capital, the conflict raging just over the bloc’s frontier presents a unique combination of threats looming large for the second half of the year.

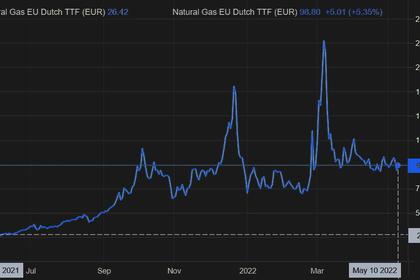

A common assumption of how that could transpire is first as a summer of worry, then a winter of woe. Concerns focus on how energy rationing and a worsening cost-of-living squeeze may test voters whose patience is already thin, and on the vulnerability of Germany’s industrial machine to shutdowns if gas supplies stop.

The officials from across the EU bureaucracy who spoke to Bloomberg for this story, often on condition of anonymity, represent a generation of policy practitioners attuned to crises from the region’s sovereign-debt turmoil to Brexit and the pandemic, giving them the perspective to judge this one isn’t yet existential.

Even so, the security realignment gripping Europe -- inflicting new pressure on public finances -- and the intensifying energy crunch is unfamiliar ground whose full consequences, according to two insiders, haven’t sunk in among decision makers and advisers pivoting from two years of the Covid-19 emergency.

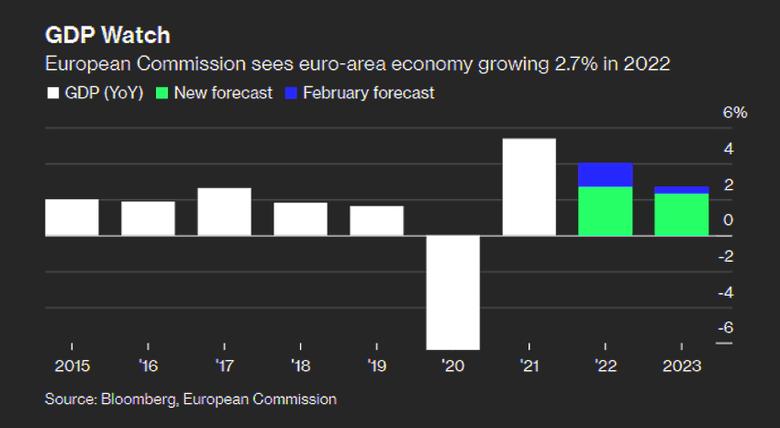

An initial crystallization of views on the economy will emerge on Monday, as the commission releases forecasts likely to acknowledge a significant slowdown in economic growth, according to a draft of the outlook seen by Bloomberg.

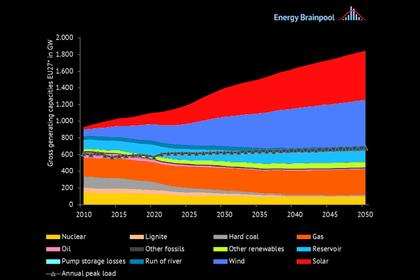

That will be followed this week by EU measures to counter the energy crunch. Later this month, a new judgment on national fiscal policies is expected to lead to a prolongation of the suspension of limits on deficits that the bloc agreed when the pandemic struck.

Among the dangers commission officials see looming, the potential of further destabilization in the market for foodstuffs has been shared between institutions. Officials worry Russian President Vladimir Putin might weaponize supplies of agri-food products, fertilizers and energy exports to inflict economic pain on the bloc.

Associated is the possibility that the coming winter might be more severe than the relatively mild one just passed. That would stoke gas demand just as Russia turns the screws, driving competition for alternative sources while potentially mobilizing discontent, particularly in countries dependent on energy imports such as Bulgaria.

Meanwhile officials are also cognizant of an influx of Ukrainian refugees now totaling more than 5 million, a tally dwarfing the refugee crisis in 2015-2016 and one causing strain especially in neighboring countries.

“We are fully aware of the social pressure,” Maros Sefcovic, the commission’s vice president for interinstitutional relations and foresight, told Bloomberg. “National governments have their hands full because of high inflation, energy prices, the huge wave of refugees. And all this brings higher costs of living.”

Against that backdrop, officials judge the multiple economic policy responses being deployed as hard to calibrate.

On the one hand, to combat inflation, the European Central Bank is likely to raise interest rates in July, maybe moving above zero later this year. Such tightening could bear down on growth and possibly further squeeze indebted families.

The ECB faces a “very complicated dilemma,” Governing Council member Olli Rehn, a former EU commissioner for economic affairs, told reporters in Salzburg earlier this month. “We are facing a very challenging economic environment.”

Meanwhile at national level, the level of budgetary support is mixed. Some pandemic-era fiscal stimulus is filtering through, and governments are offering varying support to insulate families and businesses from the energy shock. New military spending is a competing priority too.

At the EU level, officials have greater license than before to offer help, with full coffers of funds and no austerity dogma constraining them as in prior crises.

But their 2 trillion euros ($2.1 trillion) of funds are largely already committed to farmers, infrastructure projects, national recovery plans and a growing list of new priorities ranging from energy independence to joint defense projects.

The commission has granted flexibility to countries to offer subsidies to companies in the aftermath of the invasion, and is discussing how to redirect spending to energy independence and other critical areas. That could include reprogramming some of the 220 billion euros remaining in their Recovery Fund.

The energy package due this week may include measures to address the increasing household costs and energy poverty.

Meanwhile the commission’s bleaker economic view on Monday will show a major cut in its growth forecast for this year from 4% to 2.7%, a draft of the outlook shows.

Officials worry how the wider consequences of weaker growth could influence voters, cognizant of how so-called “yellow vest” protests impacted the first term of French President Emmanuel Macron, who faces parliamentary elections in June.

Italy and Spain, the weakest among Europe’s largest economies, also have national ballots next year.

-----

Earlier: