BRITAIN'S NUCLEAR AMBITIONS

FT - JULY 31 2023 - For seven decades, Britain has had an intermittent policy on civil nuclear power. From the Calder Hall plant, opened in 1956, to Hinkley Point C, approved in 2016, new nuclear power has swung wildly in and out of favour, with long periods of hiatus followed by rediscovered enthusiasm. This absence of policy continuity has been to the detriment of UK energy security and industrial strategy.

The legacy of decisions ducked is that most of Britain’s current nuclear generating capacity will be retired before replacements can be built, creating an energy gap that was foreseeable, and therefore preventable.

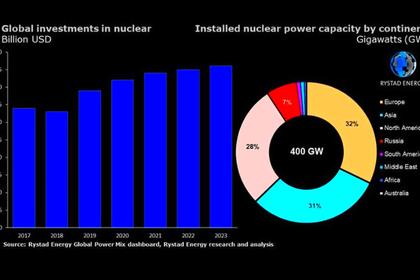

The current government claims to be all-in for new nuclear. Its Energy Security Strategy, published last year, set a target of 24 gigawatts of nuclear energy generating capacity by 2050. That is highly ambitious. To put it in context, it is three times our current capacity and nearly twice the highest nuclear capacity that the UK has ever achieved, even before Magnox plants were retired from service.

Today the cross-party House of Commons Science, Innovation and Technology Select Committee, which I chair, will publish a report endorsing the government’s decision to look to nuclear power to meet our future electricity needs — especially if we are to achieve the legal requirement of net zero carbon emissions by 2050. At a time when imported supplies of energy leave us vulnerable to price spikes at best, and shortages at worst, there is an energy security case for nuclear power under our own control.

However, we will also warn that expansive ambition will not get nuclear power built. Much more than with other energy technologies, the scale, financial demands, workforce planning and — in the case of advanced nuclear technologies — research and development needed for new nuclear requires a dependable strategic plan if hopes are to have any chance of being turned into reality.

Witness after witness who appeared before our inquiry told us that such a strategic plan for nuclear is missing. For example, there is no indication from the government on what proportion of the 24GW is intended to be met by gigawatt-scale plants like Hinkley Point C, or smaller, more distributed nuclear reactors such as small modular reactors. The government’s stated aim to deploy a nuclear reactor a year is not grounded in any explanatory detail.

The role of the new organisation, Great British Nuclear, is obscure beyond running a competition between potential developers of small modular reactors. And it is not clear whether the government wants a single supplier or several or what financial model would be used to pay for electricity generated. Achieving 24GW of nuclear capacity requires doubling the trained nuclear workforce, much of which is now approaching retirement.

In all these cases, concrete long-term commitments will be needed not just from the government but also from the nuclear industry, regulators, training and education providers and others. We call for a comprehensive Nuclear Strategic Plan to be drawn up with these participants. This blueprint should aim for cross-party political support and offers the dependability needed for private and public investment decisions to be made.

Britain has an opportunity to break out of 70 years of on-off policy towards nuclear power, with the twin imperatives of energy security and net zero favouring a substantial future contribution of nuclear to our electricity needs. But this will not happen without a clear and deliberate plan on which very long-term investors can rely. If Britain is to have substantial new nuclear capacity, there is an urgent need to turn hopes into action.

-----

Earlier: