GLOBAL NUCLEAR ENERGY RISKS

New Nuclear Energy: Assessing the National Security Risks

Sharon Squassoni April 2024

George Washington University

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

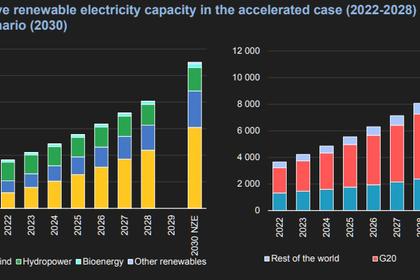

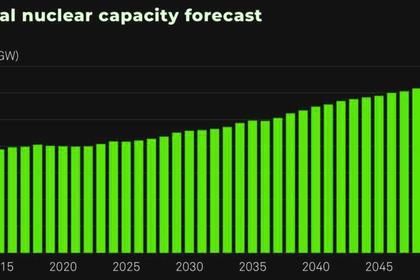

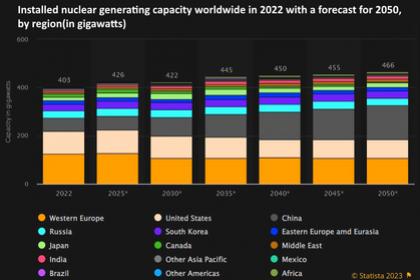

The climate crisis has renewed interest in nuclear energy as a way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In 2023, the United States and 21 other countries pledged to triple nuclear energy by 2050. Lost in the noise about meeting net

zero goals are the national security implications of attempting such an enormous expansion of nuclear energy.

The nuclear energy future that is being proposed now – small, flexible reactors distributed everywhere for many uses besides electricity – will not reduce, but will add to the national security risks that are unique to nuclear energy. On top of this, cooperation among key states essential to minimize the safety, security and proliferation risks of nuclear energy is at an all-time low.

Proliferation of nuclear weapons and nuclear terrorism are the top two security risks associated with nuclear energy. To limit those risks, nuclear energy has required a network of agreements, treaties and voluntary understandings. Even if that network were perfect – and we know it is not by the examples of Iran and North Korea – the war in Ukraine has reminded us of the danger that nuclear power plants present when governance crumbles and the risks of sabotage, coercion, or even weaponization skyrocket.

To date, the concentration of nuclear power in fewer than three dozen countries worldwide has also helped limit these risks. Yet a highly nuclearized world will present more targets across the globe and some of these will be in countries with fragile governance and limited experience and resources. Proposals to widen applications of nuclear energy beyond electricity will require fuels and technologies that require reprocessing -- a sensitive fuel cycle technology that increases proliferation risks. Absent a concerted effort to restrict sensitive fuel cycle technologies, proliferation risks will inevitably rise.

The call to triple nuclear energy coincides with the disintegration of cooperation, the unraveling of norms and the loss of credibility of international institutions that are crucial to the safe and secure operation of nuclear power. The United States should avoid turning its nuclear energy export competition with Russia and China into great power competition. Rather, it should seek to reinvigorate a shared understanding of the risks of nuclear weapons proliferation with those key countries. In particular, the United States should convene an international study on the national security risks of small modular reactor designs.

U.S. government promotion of nuclear power needs to be informed by objective, technologybased assessments as well as geopolitical analysis. The U.S. State Department should commission a new International Security Advisory Board study on how the national security risks posed by nuclear energy have changed over the last two decades and broaden its focus to include not just proliferation but also the prospects for nuclear terrorism, sabotage, coercion and weaponization of power plants.

For itself and other countries, U.S. climate objectives should not favor specific technologies but focus on the most efficient and most feasible measures to achieve net zero in the shortest amount of time. Above all, the United States needs to weigh nuclear solutions to climate change against other low-carbon options that pose fewer national security risks and may be more resilient to disruption. If the international security environment further degrades under the stresses of extreme climate, it may become increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to carve out “safe zones” for nuclear power plants.

-----

Earlier: